1177: Thou Shalt Eat Bread

An article by Kenneth John Smith, 1 Earshader from the "Eilean an Fhraoich" annual.

WHEN Adam and Eve fell from the state in which they were created they were given the command: Thou shalt eat bread’. There is no doubt whatsoever that the change from being fed from the fruit of the trees in the Garden of Eden to being fed by bread, which at that time was never baked, must have been quite dramatic. Whatever method Adam and Eve used to grind seed into meal so as to make bread is quite unknown to us.

Certain discoveries, however, have been made so as to testify to us that primitive man had a stone made vessel in the shape of a bowl into which he put his seed, and he mashed this seed with a stone made mallet so as to grind this seed whether it was oat barley or wheat and thereby he made bread. It has also been discovered that primitive man in the absence of a girdle used a flat stone which he put on top of hot cinders. He spread his dough on top of this hot flat stone, and by this method he made the required bread. This type of stone was called in Gaelic ‘Leac Aran’. I have heard it mentioned that in the event of a girdle being cracked or broken that a ‘Leac Aran’ was used as a make shift, and it appears that it could bake excellent bread.

No Spirit Level for Primitive Man

The use of the stone bowl and the stone mallet was a very slow process and primitive man through time came to use a quern which is a hand mill or, in Gaelic, ‘Brath’. The quern was a set of circular stones approximately three feet in diameter which fitted one on top of the other. They were approximately four inches thick. The bottom stone was fixed while in use on the floor of the home and it had to be level. As they had no spirit levels in these days, the method they had to ensure that the bottom stone was level was to put a bowl full of water on top of the bottom stone and when the water was level on all sides of the bowl the stone was then in its place. The top stone had two holes bored through it, the larger hole in the centre into which the grain was poured and a smaller hole in the side into which a handle was fixed. The grain that was to be ground into meal by the hand mill had first of all to be dried and hardened, and in Gaelic this was called ‘Tireadh’. This was done by putting the grain in to a cast iron pot and placed very near the fire, and this grain had to be kept moving for a certain period by hand until it was ready to be ground by the hand mill.

This grain was then poured into the centre hole of the top stone and at once one had to start moving it in circles. It appears that there was an art attached to this work for it is understood that one slip is the person who was moving the top stone would cause the stone to loose its circular motion. This process, although it was slow, ground the seed in a very satisfactory manner, but through the years people came to look for something more efficient. So thereupon man started to find a better system. They were sure grindstones of a heavier type would partly solve the problem, but what they wanted was power. They came to the conclusion that the one and only way was water power and they made their plans as follows.

Set in Penpendicular Position

First of all, they made their grinding stones much longer than the grinding stones that were in use for the household handmills. They then with the help of the blacksmith made an iron shaft which was clinched into the top stone so as to leave it as solid as the grindstone into which its was clinched. At the other end of this iron shaft they secured a set of wooden paddles, wide enough to catch the oncoming water of a river or burn which was diverted by a channel to these paddles. The stone with the iron shaft was then set in perpendicular position on top of the other stone of similar size and shape, and when the oncoming water came into contact with the paddles at the lower end of the shaft the upper stone started to move.

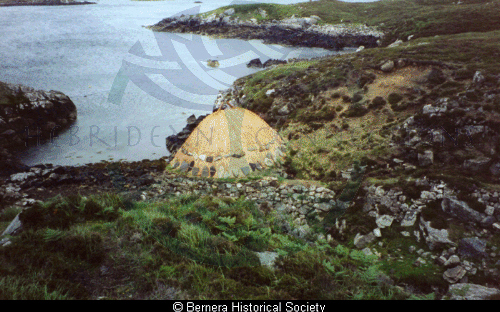

Most villages in Lewis had a small mill on their rivers or burns where they were in operation, and the name ‘Allt na Muilne’ and ‘Loch na Muilne’ are quite common in the country villages. We have ‘Ault na Muilne’ and ‘Loch na Muilne’ in Linshader and the ruins of many mills are seen on many rivers and burns all over Lewis and possibly in Harris, There is still the ruins of one of these mills on a river between Arnol and Brue, and the iron shaft that was clinched to the top stone when in use is still in existence. The same process had to be given to the grain that was used at the water mill as was taken to the grain that was ground by the hand mill — that is it had to be dried and hardened.

This was made by a process operated in a kiln or, in Gaelic, an ‘Ath’. Its operation was as follows. The grain was taken as near to a fire specially prepared for this type of work and the grain was kept in motion so that all the grain would get the same benefit of the fire. In the Island of Vuia Mhor which had seven families there is a small point quite near the ruins of the homes of the inhabitants, and it is called ‘Rhuth na h’Ath’ (The Point of the Kiln). In 1851 when Mr and Mrs Donald Mackay Domhnuill Ban and his family from Crulivig went to Canada, the Crulivig crofters converted his home into a kiln.

In Earshader, Murdo Smith, of 1 Earshader, had a kiln and was known as ‘Ath Mhurchaidh Murraich’, and the ruins of his home and where he had his kiln are still traceable south east of No. 3 Earshader. While the crofters had the use of the water mills on rivers and burns, still the crofters retained their hand mills for when the waters in the burns and rivers were to low to grind the water mills they had to use the hand mills. There is a possibility that there could be the odd person living that saw a hand mill being operated. We ourselves knew a lady who passed away some years ago at the age of ninety-two who remembered seeing one being used. Some of these hand mills were better at grinding than others, but we regret that we cannot offer an explanation for this.

By Order of the Powers That Be

The grinding of the water mills, or as the crofters called them, ‘Na Muillean Beaga’, came to an abrupt end when the Scottish Office — or its equivalent — erected mills in Lewis. One in Garrabost, one in Ness, one in Breasclete. By the order of the powers that be, all the small mills were dismantled except for a few which were left untouched, and the larger mills had to be operated. It is believed that the Garrabost mill and the Ness mill were the last of these mills to be in use. Both the handmill (the Brath) and the small water mill served their purpose well for many a healthy family were reared on the meal they produced.

It may be interesting to note that we saw a mill in Palestine being operated by the same principle as the old Lewis hand mill. In the absence of water power the mill was powered by a blindfold donkey that was harnessed to the top stone, and the animal was going round in circles for some hours. It was blindfolded to prevent dizziness. We were told that this method of grinding backdated to Biblical times.

In conclusion, some of these hand mill grinding stones are still to be seen in various villages. The last use they had was being used as an anchor in stacks of oats or barley in the crofters’ cornyard.

(T_B_Ea_02_0006)

Details

- Record Type:

- Story, Report or Tradition

- Type Of Story Report Tradition:

- Story; Tradition

- Record Maintained by:

- CEBL