41067: Personal Glimpses of Gravir IX: Entertainments

An account of life in Gravir, by Calum Macinnes, 8 Gravir.

IX Entertainments

Formal physical education did not have a place in the curriculum of Gravir School in 1926. But we found methods of expending excess energy during play times. The boys played a form of shinty (iomain or camanachd in Gaelic). We did not have regulation shinty sticks. Instead, we used old walking sticks, the crooks of which had straightened partially. The ball was the cork of a fishing net. The rules of the game were flexible, but two teams of roughly equal size battled to place the cork between the two stones that were used as goal posts. The girls had a greater variety of games, some of which involved singing, dancing or jumping. Peevers came into the last category. Skipping was fairly common among them too.

Boys played a game with buttons. A piece of wood was placed in the ground and the objective was to place a button, thrown from a marked position, nearest to the piece of wood. The person who was closest could then take all the other buttons. This game was often the cause of family friction because buttons were cut off garments that were still in use – like father’s best Sunday suit. We played outside the school curtilage sometimes. Elvers were plentiful in the river and could be caught by lifting the stones under which they sheltered. Crystals of fool’s gold ie. Iron sulphide (iron pyrites) were still obtainable in the mid-twenties in broken pieces of the Ballachulish slate with which the river bed was strewn. In the summer we competed to see who could jump across the widest pools of the river. This often resulted in injury to bare feet if the jumper failed to reach the opposite grassy bank of the river, but that didn’t seem to deter us.

Toys

My 9 month old grandson, Neil Ingram MacInnes, was sitting on the floor in their living room in Edinburgh, surrounded by all kinds of toys and learning aids. Seventy years ago, when I was the same age, there was none at No 8 Gravir. But that did not mean we felt deprived. We made them, or used natural objects imaginatively to play games. The horns of mature wedders and rams and old ewes, which we had eaten, were our toys, each one endowed with characteristic ovine attributes; some were even named. An imaginative boy could devise countless games with his toy sheep flock. We made slings – of the David and Goliath type – from string and pieces of leather from old shoes. We made spinning tops (gille-mirean) from old cotton reels. One end of the reel was shaped to a point. A cylindrical piece of wood was pushed through the centre hole at the other end. A flick of the thumb and forefinger could set the top spinning on a smooth surface. We made bows of flexible lengths of newly cut willow. We competed in unsophisticated archery games. We made, and played with, home-made cards. We made wooden boats using a penknife and sailed them on the river and on the sea when the tide came in. Indeed, far from being deprived, we made situations in which imagination, combined with the advance of practical skills, produced ideal learning opportunities for growing boys.

Girls were, of course, no less imaginative but their games were based on domestic situations. Shards of broken crockery became dishes, empty tins were pots and pans and buckets, and when they became older they made bothans – little structures made of stone, wood and straw or dried grass, and shaped like a hut or house. If they were really ambitious they enlisted the help of the boys to make structures that were big enough for them to crawl inside. The shards of crockery were often brightly coloured and called ‘bristealan’ in local Gaelic.

Music

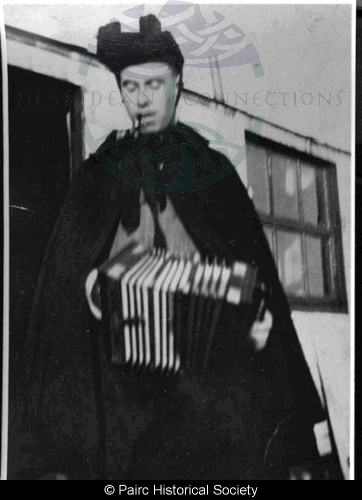

The small accordian-like melodeon was the most popular musical instrument in the twenties and thirties. It was cheap and, played by ear, with no formal tuition, a person could soon master the small repertoire of tunes required for ‘danns an rathaid’. Every village had several players who could perform with some proficiency.

Next in popularity were the pipes. Many young man had received instruction in piping in the army during the war and subsequently, if they enrolled in the regular army. The pipes came into their own during wedding processions and at wedding dances where dances like the Eightsome Reel were popular.

The mouth organ and the Jew’s harp (tromb) were also popular and, in the absence of a greater variety of musical instruments, some resorted to squeeze music out of the comb!

But the best music in South Lochs comes from the human voice. Some, like Calum Kennedy of Orinsay and Donald Macrae of Kershader have prospered on the concert stage. Others, like Murdani (Mast) Kennedy sing about local issues in a humorous and droll way that is much appreciated by South Lochs audiences. All of them have fine voices as have the large numbers of men who precent the Psalms at Free Church services. Notably among them are the four Maclennan brothers from Marvig: Murdo, Duncan, Murdo John, and Donald. Indeed, all the church officials seem to blossom as precenters when they achieve the ranks of eldership and deaconship, leading to the hypothesis which I once expressed to a minister of my acquaintance, that elevation to church office brings with it a corresponding improvement in the vocal chords!

The Tigh Ceilidh

There is no evidence that the art of the story teller (sgeulaiche or seanchaidh in Gaelic) flourished to any great degree in South Lochs – certainly not to the extent that it flourished in the southern isles of the Hebrides. But there were many interesting raconteurs. Included among them were former sailors who had spent most of their lives working for shipping companies and others who had been in the regular army. My recollection is that there were no designated ceilidh houses in the mid-twenties but visiting other houses at night was a common practice. The raconteur operated at this own fireside and told his yarns repeatedly to the visitors. Some raconteurs were given a high degree of credibility; others were inclined towards exaggeration and were apt to put an element of imagination into their yarns, but all were interesting in their own way, and helped to while away a winter’s night in congenial company.

Tales of adventures on the high seas and on the battlefield were interspersed with ghost stories. Some of the ghost stories were believed, especially by the young members of the audience who were often reluctant to walk home unaccompanied by adults on a dark moonless night.

Comhairle nan Eilean adapted the name Tigh Ceilidh for the meeting halls in their fine Sheltered Housing schemes.

Drama

There were few opportunities to see anything that could be classed as drama in the mid-twenties. In the early thirties however, a form of drama, the short 5 minute or 10 minute sketch, became popular. It was made popular by the Gravir Concert Party, a body established with the primary aim of collecting funds to enable them to buy the district nurse a car to replace her bicycle. Concerts were held in the schools of South Lochs. The programmes consisted mainly of solo singing of Gaelic songs, some piping, some melodeon playing and sometimes a short sketch.

The principal exponent of the genre was Murdo Matheson, No 25 Gravir, whose alter ego, Cailleach an Deacoin, was based on a film character of the time called Old Mother Riley. This part was played by a male actor in drag. Murdo used topical events to build comic cameos in which he had the leading part, and some of his young acolytes had supporting roles. The audiences loved these sketches. Later, Murdo, using the same drag personification, became a solo performer and was popular with audiences at concerts held in venues throughout the island by the Gravir Concert Party.

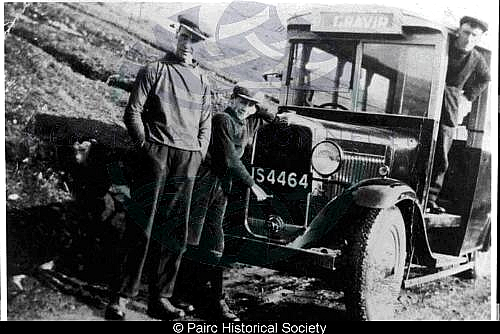

Eventually sufficient funds to buy a Mini for the nurse were collected and the car duly appeared. The nurse was generous in offering lifts to the people of the district but the Free Church minister, Rev Mr Macleod, would not accept a lift because the money to purchase the car was obtained by holding concerts. He was a fine man, but rigidly inflexible in his principles! One story involving Mr Macleod concerns Murdo Alex Morrison the occasional driver of the first ever Gravir bus (a seven-seater). Murdo was told by Mr Macleod that he would travel with him to Stornoway the following day ‘ma bhios me beo’ (if I’m alive). Murdo stopped at the manse on his way to Stornoway and, when the minister did not appear, said – with no great seriousness – that the minister must have died during the night. The story soon spread among the fishing fleet in Stornoway and some of the Gravir boats were on their way home to Gravir when it became known that the story was a hoax!

Although Mr Macleod would not accept a lift in the nurse’s Mini, in later years he used to charter the lorry owned by Donald MacAskill, Lake House (Domhnall Alein) to drive him between villages.

Details

- Record Type:

- Story, Report or Tradition

- Type Of Story Report Tradition:

- Reminiscences

- Record Maintained by:

- CEP